|

Giovanni Boldini: Peering into the Soul |

| On the occasion of the 90th anniversary of Boldini’s death in Paris in 1931, Palazzo Albergati of Bologna is hosting a major exhibition dedicated to Giovanni Boldini, with more than 90 magnificent works, from 29 October 2021 to 13 March 2022. |

| Related images (16) |

|

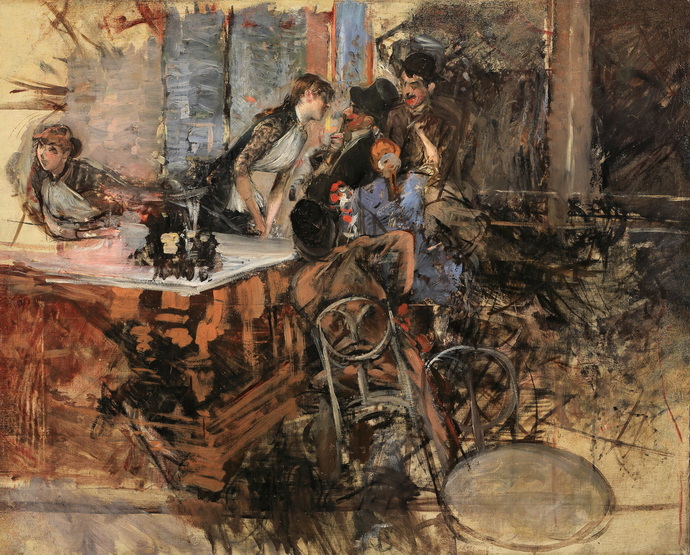

Fascinating women, swirling gowns, and the atmosphere of the Belle Epoque: such was the world of Boldini, one of the most beloved Italian artists of all time, celebrated with a major exhibition in Palazzo Albergati of Bologna. Giovanni Boldini’s passionate world was defined by the fascination of women, their splendid, swirling dresses and the Belle Epoque with its salons. More than any other painter, Boldini was able to brilliantly recreate the rarefied atmosphere of that extraordinary epoch. Literature and fashion, music and luxury, art and bistrots all merged in a sensual can can rhythm, producing a remarkable social and civil reawakening. The anthological exhibition Giovanni Boldini. Lo sguardo nell’anima (Giovanni Boldini: Peering into the Soul), organized simultaneously along narrative/chronological and thematic lines, presents a rich selection of works that best represent Boldini’s style, his ability to exalt the unique quality of female beauty and reveal the most intimate, mysterious soul of leading aristocrats of his time. On display are celebrated works such as Mademoiselle De Nemidoff (1908), Portrait of the Actress Alice Regnault (1884), Countess Beatrice Susanna Henriette van Van Bylandt (1903), Countess De Rasty Reclining (c. 1880), La camicetta di voile (The Blouse of Voile) (c. 1906). In addition to Boldini’s international and creative life and work, the exhibition includes a significant number of works for comparison by his contemporaries Vittorio Matteo Corcos, Federico Zandomeneghi, Gustave Leonard De Jonghe, Raimundo de Madrazo, Pompeo Massani, Gaetano Esposito, Salvatore Postiglione, José Villegas I Cordero, Alessandro Rontini, Ettore Tito, Cesare Saccaggi, Paul Cesar Helleu and Giuseppe Giani. Curated by Tiziano Panconi, the world’s leading Boldini expert, the exhibition is supported by the Region of Emilia Romagna and the City of Bologna, and is produced and organized by Arthemisia and Poema, in collaboration with Museoarchives Giovanni Boldini Macchiaoli di Pistoia, under the aegis of the Study Commission for the 90th Anniversary of the Death of Boldini (1842-1931). In fact, the “anniversary” exhibition takes place in the context of the celebrations of the 90th anniversary of Giovanni Boldini’s death, under the aegis of the study commission appointed by the City of Ferrara and Fondazione Ferrara Arte. Chaired by Vittorio Sgarbi and directed by Tiziano Panconi, the commission includes the highly respected experts Beatrice Avanzi (Mart, Rovereto), Loredana Angiolino, Maria Teresa Benedetti, Pietro Di Natale (director Ferrara Arte), Almerinda Di Benedetto (Università Luigi Vanvitelli, Naples), Elena Di Raddo (Università La Cattolica, Milan), Leo Lecci (Università di Genova), Marina Mattei, Gioia Mori (Accademia di Belle Arti, Rome) and Lucio Scardino. The exhibition is sponsored by Ricola The exhibition GIOVANNI BOLDINI. Lo sguardo nell’anima also participates in the “L’Arte della solidarietà” project, realized with Susan G. Komen Italia – the exhibition’s charity partner. The essence of the project – with the pink of Komen Italia appearing among the masterpieces in the exhibition – is to unite art and health, beauty with prevention. More importantly, part of the proceeds from ticket sales will be donated to specific health protection projects. In this case, the funds will serve to acquire “helmets” to be worn during chemotherapy to keep the patient’s hair from falling out, an issue of great concern to women. THE EXHIBITIONBoldini the enchanter, Boldini the faun, Boldini the painter! The insolent little man with the Italian accent strolling through Paris was all this and more. From beneath his bowler hat, he looked each person over from top to bottom, returning their greeting with a slight grimace of annoyance. Son of the modest painter-restorer Antonio, he understood distress, having experienced the humiliation of misery, of his tiny body compressed into a height of a mere one meter fifty-four, disdained as a match for his one great love, Giulia Passega, who married a respectable young man employed in the prefecture. Indeed, Boldini should be understood as a young man of the Po Valley province who rose from below to enter the salons of high society in the very heart of civilization and of an epoch that would eventually consecrate him as one of its most iconic protagonists. In the centennial of his death (Ferrara 1842-Paris 1931), this exhibition highlights the artist’s capacity to psychoanalyze his subjects, his “divines”. As they posed for hours, seated before his easel for days on end, he never tired of asking the most improper questions until he truly understood them and could capture their spirit and peer into their soul. To be portrayed by Boldini meant throwing off the mantle of aristocratic pride with which every great lady worthy of her own coat of arms was so richly endowed. They had to play along and accept his provocations, responding in kind to his premeditated insolence. They surrendered in the end, however, even if only mentally, bringing down the ideological wall of arrogance behind which lay a perilous fragility. During the days of immobile posing, conversing and confessing, the “faun” granted himself the luxury of intentionally stalling, listlessly drawing lines on the pages of a notepad to observe and better understand them or sketching a study on a small panel. Eventually, when the intimacy reached a point where his subject would soften her attitude, or break out in liberating tears or, more often, in neurotic behaviour or unrestrained arousal, the artist’s predatory fire would ignite. Boldini was able to seize the moment, the very instant when a sincere gaze revealed the deepest feelings of his prey and her body language became more expressive - – the instant when one action becomes another, when the power behind one gesture dies out to quickly regenerate in the next. In his maturity and old age, Boldini’s long, swirling brushstrokes applied with vigorous slashes of colour gave a new dynamism to the bodies of his “divine” creatures. In effect, his style – simultaneously classic and modern – represented a perfect response to the aesthetic and progressive inclinations of the upper class of his time. The more than 90 works in the exhibition are organized into seven thematic sections – The journey from Ferrara to Florence, en route to Paris; The Maison Goupil; The end of relations with Berthe, Gabrielle and the cafè chantant; “Breath of life” – from portraits to landscape; The sign as the structure of a style; Fin de Siècle style and The nouveau siècle – following the years of Boldini’s artistic activity and documenting the complete expressive arc of his career.

Section 1 - The journey from Ferrara to Florence, en route to ParisIn 1863, Boldini obtained 29,260 Lira as part of the inheritance left him years before by his paternal great-uncle. Thanks to this influx of funds, in the space of a few months in 1864, he was able to leave Ferrara forever and move to Florence, the leading cultural and artistic centre of the period, where he came into close contact with the Macchiaioli and developed decisive friendships like that with Telemaco Signorini. The early phases of the artistic activity of the highly precocious Giovanni Boldini – that is, the period in Ferrara from 1857 to 1864 – was dominated by his potent, contentious relationship with his father, the painter Antonio Boldini. Nonetheless, the twenty-year-old painter was able to appreciate the change in the political and social climate which had begun with the annexation of Ferrara into the new state of Savoy as a result of the 1860 Plebiscite. The positive effects made themselves felt immediately in the form of a new cultural ferment and renewed hedonism that emerged in opposition to the gloomy and stagnant penitential climate under the previous Papal domination. Giovanni absorbed all this excitement like a sponge, even if, given his youth, he tended to express it in predominantly playful and amorous ways. He formed relationships with young women in Ferrara, whose portraits he sometimes painted (as in the romantic La pensée), attended parties and popular meeting places, dressed in suits created by Delfino Santi – the most sought-after tailor in the city – and generally freed himself more and more from his father’s influence. In 1866, Boldini presented two paintings in his first collective exhibition, organized by the Società di Incoraggiamento in Firenze. Telemaco Signorini wrote perceptively of his work, pointing out that Boldini avoided the convention of making the subject’s face stand out against a uniform background (as done in Ferrara by Giovanni Pagliarini, the finest local portrait painter). Section 2 - The Maison GoupilAfter being based in Florence and traveling between Ferrara, France and England, Boldini moved definitively to Paris in October 1871. He lived at first on Avenue Frochot and later on Place Pigalle with his partner and model Berthe. At this time, he also began a close collaboration with the powerful art dealer Adolphe Goupil, which lasted until 1878. Boldini was fascinated by the charismatic Marià Fortuny i Marsal – leading painter of the Maison Goupil before him – and by his dazzling graphic textures. In his paintings, Boldini recognized a decisive move along the road to much-awaited progress as well as a welcome opposition to the concept of separation between a work and its author, who was supposed to disappear into the text, according to the Verismo theorized by Capuana. In this way, the author’s opinions are silenced so that the events unfold in perfect autonomy, transcribed as a faithful moralizing mirror of reality. Fortuny’s folkloric Spanish style also influenced the period of painting of Italy’s Mezzogiorno. So, for example, Michetti laid out his eloquent exaggerated colours in no uncertain terms in Corpus Domini, whose rhetorical tones were reflected in D’Annunzio’s later parlance. For his part, Boldini had partially defused the Fortuny prototype, altering its particular meanings, especially its ornamental nature, and transcribing it in an extremely complex and varied lexicological context. He was able to distance himself from Fortuny more easily in the portraits, thanks largely to his astonishing technical mastery, which allowed him to overshadow even the brilliant Catalan, with whom he alternated as lead painter of the Maison Goupil in the early 70s. Echoes of Fortuny’s style did not resound for long in Boldini’s work, however. By the end of the ‘70s, those descriptive formulas that had previously been so successful were completely upended by the unmistakeable crescendo of his dynamic sensibility. The dazzling salons of the magnificent aristocratic homes where he had chatted delightfully with ladies and marquises vanished forever from Boldini’s imagery, and with them, the Empire style and social confidence that had defined the French high bourgeoisie until then. Section 3 – The end of relations with Berthe, Gabrielle and the cafè chantantThe true “artist’s homes” could be found on the rive droite of the Seine, in the area between the hill of Montmartre and Place Pigalle – where the peintre italien lived at Number 11 until 1886. Here was the bohémien life and decadent atmosphere of the narrow roads winding between the clearings and vineyards of the old agricultural province, where the evening opened its curtain onto the scandalous demi-monde, bathed in alcohol and packed with prostitutes whose regular clients were none other than the husbands and “irreproachable” fathers of the French bourgeoisie who scorned them by day. Boldini’s last portraits of Berthè were painted between 1878 and 1880, although his affair with the model lasted at least until July 1881, as implied by Signorini in his travel notebook: “…at the inn waiting for Tivoli to go to the countryside to Boldini’s place. I reached Chatou near Bougival and saw Boldini and Berta…” Apparently, though mysteriously, one of the happiest chapters of the artist’s life ended more or less in this period. After a full decade, that charming young woman, so seductive and aristocratic by nature, Boldini’s first true divina, was definitively replaced by Gabrielle, her rival in love. Actually, Boldini had been meeting Gabrielle secretly since 1875 in a rented on rue Demours. During these secret rendezvous with the noblewoman, wife of Count Costantin de Rasty, Boldini painted her sensual, mysterious beauty in portraits exuding the intoxication of passion and an insistent psychological tension generated by being aware of the danger yet overpowered by sensuality. “She is beautiful, brunette and passionate. High-ranking and married, too. A friend welcomed in the best salons, who knows everything about everyone, an adorable gossip, amusingly wise, before whom the female experience and subtle cunning of poor Berthe seemed mere childish, naïve instincts.” Transported by the maelstrom of passion, the artist, for the first time, found himself almost involuntarily moving recklessly along an uncensored narrative path, unknown to him, mediated only by the elegance of his style. It was almost as if he believed that the creative and cultural projects pursued at the end of his clandestine encounters with Gabrielle could redeem or return dignity to that grim relationship, founded on the betrayal of a partner and a husband. In fact, the aspirations of an entire generation of women embodying the spirit of modernity flourished in the cosmopolitan Ville Lumière with its café-chantant and its Impressionist painters. Artists like sculptor Camille Claudel or painters Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt as well as writers, actresses and singers, or simply eccentric protagonists of their day, lived out their condition as women with a new sense of independence. Section 4 - The “breath of life” – from portraits to landscapeThe extraordinary arrival in Paris of hundreds of painters, each tormented by the obsessive need to discover original views and subjects, gave rise to an unprecedented sort of “mass study” – verging on psychoanalysis – of the places, environments and behaviour of that heterogenous population. As an expert Casanova, Boldini entertained his models in his studio, trying to break through the usual etiquette with pungent boutades that were clearly out of place. Taking his models off-guard in this way, he managed to orchestrate unexpectedly confidential and provocative conversations, spiced with titillating repartee. Completely unabashed, he prompted easy laughter to loosen the hold of inhibitions, overcoming the embarrassment of his muses, who felt disconcerted and obliged to respond in kind. He professed admiration for them in a barrage of puns and paraphrases. At times he attacked them, brazenly questioning their moral integrity, interrogating and making not-so-subtle propositions that would never be tolerated normally by a lady of noble virtue; at others, equally malicious, he called upon their compassion, lamenting their lack of consideration of the artist and, more pointedly, of the man. Amidst the questions, the more fragile souls vacillated, at times erupting with torrential confessions about their condition as misunderstood and unsatisfied women and wives. In this way, the “sensitive friend”, the seasoned amateur, the grand maître peintre, mesmerizing guardian of arcane secrets of beauty and female charme, would whisper some helpful suggestions to reignite the fire of their lost passion. Section 5 – The sign as the structure of a styeBoldini was a highly accomplished draughtsman as well as a painter. Like a master of old, he duplicated facial features and perspectives with his pencil or burin, outlining the shapes of his subjects. His incisive, mobile lines imparted vitality, captured expressions and precisely recorded the light caressing the faces of his subjects. “One day,” wrote Francesca d’Orsay in her memoirs, “Carlo Pacci came with us to Boldini’s place on Boulevard Berthier. I had seen the Whistler in Venice [she is probably referring to Boldini’s portrait of Whistler exhibited in the 1905 Biennale, Author’s note]. In his studio, Boldini was fascinating. One had to wonder how such a small man could create such great works. The painter’s mean, standoffish attitude soon shifted from sullen to charming. He told me that he knew Palermo, where he had done a portrait of my cousin Franca Florio, and then digressed to tell me that I resembled her. He always mumbled when he spoke, but in the end, he was amusing, clever and original. “I want to do your portrait,” he announced, staring into my eyes. First he did some drypoint. As the diamond etched the copper plate, a golden light was reflected in his glasses that lit up his body, just as in certain paintings by the Flemish masters of studio interiors. We went to his studio every day, and he did his work with me. Once while he was drawing, he cried, “No! I don’t need new colours. Your colours are already too beautiful […]” Boldini was able to seize the moment, that irreplaceable moment when a sincere glance revealed the deepest feelings of his prey and her body language became more expressive – the instant when one action becomes another, when the power behind one gesture dies out to quickly regenerate in the next. Secction 6 - Fin de siècle styleBoldini possessed a special allure, wrapped in an air of mystery, and his repartee fed into the myth of the unattainable woman, characterized by the esprit des Guermantes. His fiery outbursts served as a warning of haughtiness for the other, the same self-importance alive in the eyes, the perfectly balanced postures and fashionable attire of his femmes divines. Countess Greffulhe, daughter of Joseph de Riquet de Caraman, Prince of Chimay, and wife of Viscount Henry Greffulhe, heir to a financial and real estate empire, planned her public appearances with great care, presenting herself with the most elegant and at times eccentric dresses made of tulle, gauze and muslin, perhaps with feathers, or a fabulous original kimono, topped with velvet robes with Oriental motifs designed by Wroth, Fortuny, Lanvin and Babani. Although manifestations of extreme egocentrism such as those of Countess Greffulhe were often criticized, they still enjoyed widespread approval and represented an anticipation of the ongoing, unstoppable process of women’s emancipation. In 1901, in one of the most iconic portraits of his artistic career, Boldini painted Cléo de Mérode, ballerina of the Paris Opéra, famous for her ethereal beauty. Daughter of Baroness Vincentia de Mérode and a high-society Austrian gentleman who never recognized her as his daughter, Cléo was timid and introverted, altogether different from most of her fellow dancers, who, by the very nature of their profession, tended to be boisterous and eccentric. Cléo, on the other hand, was demure and the peak of elegance, dressed in garments by Jacques Doucet. Sometimes, during pauses in the dance, she could be found off by herself reading a book. She had no love for the demi-monde, but her popularity irritated some of the famed courtesans. One of these, Liane de Pougy, in her roman à clef entitled Les Sensations de Mlle de La Bringue, described “Méo de la Clef” as a Mademoiselle who “personifies love without making it”. Little Cléo’s exceptionally photogenic quality and her sensual, graceful poses made her a model with a particular emancipated beauty, capable of fascinating artists of the likes of Gustav Klimt, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Edgar Degas and, of course, Boldini, who portrayed her in an image of universal modernity and elegance. Section 7: The nouveau siècleBoldini depicted his women in the moment just before their beauty would fade forever, before they entered the autumn of their lives and their fragrant rose petals would begin to fall. At times, like a magician, he collected the fragile petals and lovingly recomposed the wilting flowers, offering them an instant of eternal spring. In his portraits of these women, Boldini incapsulated an epoch, La Belle Epoque, first that of his youth, when opulent gay Paris was enjoying the exhilaration of economic well-being and social progress and later, that of old age and decadence, when the First World War blocked the publication of fashion magazines, and the master found himself irretrievably aged. “…Milli fell under the mysterious spell of that little man with his hypnotic gaze that had so many stories to tell, of that older gentleman with thinning blond hair, a fresh mouth and large, lively blue eyes. She listened to him speaking for hours, seated on the bergères where the divine muses of that diabolic portrait artist had sat before her. Now, here he was, his vision failing, sheltered in the warm light of those walls from which the luminous faces of his women emerged like ghosts or stars in a firmament that has set forever. Observing them, one heard the ‘… voices, voices of dead or aged women, voices of female admirers, friends and lovers… Vous rappelez-vous, Boldini?, seemed to come from the painting with the ample bust of the lovely Madame J. de C., whose aged voice we heard repeating that anguished question with forlorn monotony, like the cry of the damned remembering life… Vous rappelez-vous, Boldini?...’” With the greed of a Mephistopheles, for over sixty years, Boldini managed to have the most fascinating women of French high society take their turn on his Empire chairs, immobile and intimidated under the rapacious stare of the genius, who – paraphrasing their dialogues with a touch of artistry and speaking of the very stories they wanted to be kept silent – flattered them and encouraged them to express themselves unreservedly because surely, to an artist as to a doctor, one must confide everything. He was inebriated by the fragrance of their perfumes and absorbed the essence of their controversial personalities. Then he mercilessly wielded his brush to strike the blow, overpowering the supposed respectability that his sophisticated subjects had hoped to display when they first entered his studio. | |

Munch: The Scream Within

Munch: The Scream WithinOne of the year’s most eagerly awaited exhibitions to open its doors on 14 September 2024: Edvard Munch is back in Milan with a major retrospective after a 40-year absence.

In the garden

In the gardenThe initiative, which is scheduled to run from June 26th to September 13th, 2020, is inaugurating a temporary space for art in Corso Matteotti 5, in Milan, in the very heart of the city.

Perugia Travel Guide

Perugia Travel GuidePerugia is the chief town of Umbria. This beautiful town is sited on a hill in the middle of a verdant country. His central square is considered one of the most beautiful squares of Italy and history, traditions, art and nature make a unique ensemble in this town as in the whole