|

Monet: Capolavori dal Musée Marmottan Monet |

| A great exhibition entirely dedicated to CLAUDE MONET opens at the Vittoriano in Rome till June 3th 2018 |

| Related images (15) |

|

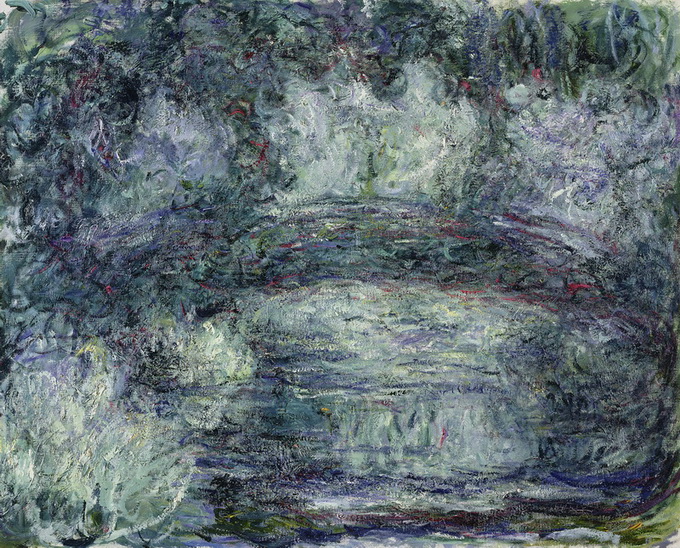

The exhibition includes about sixty paintings which Monet was particularly fond of and which he kept in his last and much-loved home in Giverny: an extraordinary loan from the Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris, an institution that in 2014 celebrated its eightieth anniversary and that holds the most important and extensive collection of works by the French painter, based on the donations from collectors of the time and the painter’s son Michel. Weeping willows, a path under rose trellises, a Japanese footbridge, monumental water lilies, wisteria flowers, evanescent hazy colours, French countryside, and nature in all its seasons: all subjects the artist handled with striking modernity in the many masterpieces presented in this exhibition such as Portrait of Michel Monet as a Baby (1878-79), Water Lilies (1916-1919), The Roses (1925-1926), and London, Parliament, Reflections on the Thames (1905). Under the aegis of the Institute for the History of the Italian Risorgimento, the exhibition is promoted by the Capitoline Superintendence for the Artistic Heritage of Rome – Department of Cultural Development, with the patronage of the Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities and Tourism (MiBACT) and of the Regione Lazio, and has been organized and produced by Gruppo Arthemisia in collaboration with the Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris. Curated by Marianne Mathieu, the art historian deputy-director of Musée Marmottan responsible for the Monet Collection, Monet is an exhibition describing the entire artistic career of the master of Impressionism, from his earliest works – the famous late 1850s caricatures with which he earned his first money making a name for himself in his hometown Le Havre – to his rural and urban landscapes of London, Paris, Vétheuil, Pourville, also including the works he produced in the many places he visited, including Liguria, as testified by the painting of the Castle of Dolceacqua also on display. The exhibition also includes portraits of Monet’s children and the famous canvases capturing the flowers of his garden, a place the artist knowingly perfected and landscaped through the years: had he not become a painter – Monet confessed – he would have become a gardener, stating that without flowers he would never have taken on painting. The display also comprises Monet’s exceptionally modern depictions of his weeping willows, of the garden path under rose trellises, the Japanese footbridge, and the monumental water lilies dissolving into a violet haze and the dim glow of fog.

Everything has already been written and said about Claude Monet’s paintings – historians and enraptured visitors filled with admiration are to be credited for that – yet Guy de Maupassant’s words still offer a compelling description of what this artist’s “new” and unprecedented style meant for the art world of the time – an art that still leaves viewers breathless today: “Last year, in this town, I often used to follow Claude Monet while searching for his “impressions”. He didn’t act much like a painter but rather like a hunter. He would go followed by children carrying five or six of his canvases all representing the same subject at different times of the day with different light effects. He used to work on them in turn, according to the changes in the sky. Standing before his subject the painter would wait for sunlight and shadows, capturing the sudden ray of sun or the passing cloud with a few strokes of his brush and, defying all things false and conventional, he would rapidly put them down upon the canvas.” Monet transformed en plein air painting into a life ritual, devoid of any mediation. Working in blazing sunshine or pouring rain, tracking the slightest variations in the weather under the imperious rule of the sun, he transformed colours into pure brushstrokes of energy. In his canvases we see the dispersal of nature’s rational unity into an indistinct, ephemeral yet dazzling flow. The exhibition shows the many facets of Monet’s production, fully reflecting the value of this great master who through his art was capable of translating nature onto a canvas by capturing its essence and vital spirit. Once again Maupassant’s words are of assistance: “I have seen him capture a scintillating fall of light upon a white rock, fixing it with a pouring of yellow brushstrokes that oddly conveyed the sudden and fleeting effect of this elusive and blinding blaze. Another time he seized a rainstorm beating down upon the sea casting it upon the canvas. And it was truly rain he painted, nothing but rain obscuring waves, rocks, and sky that could just about be seen beneath that deluge”. The exhibition also includes a re-creation of one of Claude Monet’s famous Water Lilies, the series that changed the history of painting and that was to influence generations of artists to come. In 1958, a terrible fire inside the Museum of Modern Art in New York severely damaged several works: among these was a number Monet’s paintings that were lost forever. Thanks to a unique and ambitious project made possible by the use of highly advanced technology, Sky Arte HD One has been able to re-create one of these masterpieces – Water Lilies (1914-26) –, which is here publicly displayed for the first time. The captivating story of this painting and the process of its re-creation are the focus of the Sky Arte HD international production entitled Il Mistero dei Capolavori Perduti (The Mystery of the Lost Masterpieces), a series of seven documentaries directed by Giovanni Troilo and co-produced by Ballandi Arts, each dedicated to a lost painting that was either stolen, or accidentally or deliberately destroyed: lost masterpieces that will soon come back to life on Sky Arte HD. EXHIBITION SECTIONSA Family – A Museum Monet loved children. His first wife Camille Doncieux, who died prematurely aged only thirty-one in 1878, gave him two sons, Jean and Michel. His second wife Alice gave him six stepchildren (Marthe, Blanche, Suzanne, Jacques, Germaine and Jean-Pierre) born from her first marriage to Ernest Hoschedé. Monet made no difference between them and always signed all his letters to them with the same words: “A loving kiss, your old father Claude Monet”. Family played a key role in the artist’s life, Monet gave great importance to it. Raised in Le Havre, Monet left his family home and moved to Paris to complete his artistic training and against his parents’ will he soon set up a family with Camille, the model he eventually married in 1870 when Jean, the firstborn was already two years old. After Camille’s death, the artist started a relationship with the wife of his art patron and the couple and their “extended family” settled in Giverny. Throughout his career, Monet painted very few portraits, most of which are of his children, a circumstance which goes to prove his great love for his offspring. Monet never ceased painting loving portraits of his first two sons. Jean, the elder, was one of his recurring sitters. The Portrait of Jean Monet (1880) painted when the boy was thirteen is particularly touching because it is the last portrait his father ever painted of him. There are three surviving portraits of Michel, which are all included in this exhibition: Portrait of Michel Monet as a Baby (1878-79) at one, Portrait of Michel Monet in a Pompom Hat (1880) at two and a half, and Michel Monet in a Blue Jumper (1883) at five. In the first portrait dating from the winter 1878-1879, we see a chubby-cheeked baby captured with rapid hasty brushstrokes, since it is impossible to make a child that young pose for very long. The painting’s sketchy and extemporaneous quality is underlined by Monet’s deliberate decision to leave some parts incomplete. Caricatures When he was ten, Monet was sent to a boarding school in Le Havre where drawing classes were held by Jacques François Ochard, an elderly teacher who had once been one of David’s students. Ochard’s lessons proved crucial for Monet who at that stage started to make sketches and caricatures that he liked to give to his schoolmates. These caricatures eventually became rather requested and Monet took advantage of the situation charging ten or twenty francs a piece. We know he earned about two thousand francs for about one hundred works, but so far only a few of them have been found. Many of these caricatures – as in the case of Old Woman from Normandy (1857) or Young Woman at the Upright Piano (1858) included in the exhibition – were “types” rather than depictions of real people. Every Sunday, Monet used to present five or six new caricatures set in a golden frame in Gravier’s stationary shop in Rue de Paris where a merry and appreciative crowd would gather to try and guess the identity of those depicted. Monet, who would often attend these presentations, is known to have said that the attention made him feel very proud. In order to improve his style Monet also used to make copies of portraits by affirmed artists which were published in periodicals such as Le Gaulois, Le journal amusant, and in Panthéon. These studies, which the artist kept in a folder and never sold, portray famous personalities such as French author, playwright, and librettist Adolphe d'Ennery or Dennery, author of The Two Orphans, journalist and art critic Théodore Pelloquet, writer Jules François Félix Husson, known as Fleury, but better known as Champfleury , who wrote numerous essays on the history of caricature, and the very famous dramatist Eugène Scribe whose works are still represented on stage today thanks to his brilliant vaudevilles that constitute the backbone of the Théâtre du Gymnase-Dramatique which Scribe himself co-founded in 1820. Monet, the Impression Hunter Before finding his perfect location and ideal subjects in Giverny, Monet explored the French countryside far and wide often even travelling abroad in search of a subject that would capture his attention, something he could observe and depict in different conditions. In 1870 in London, a city where he would return another three times, he discovered the works of Constable and Turner whose research on the ever-changing effects of light made a deep impression on him. Turner’s production was in fact crucial to the genesis of Impressionism and of works such as Charing Cross Bridge (1899-1901), Charing Cross Bridge, Smoke in the Fog (1902) and London, Parliament, Reflections on the Thames (1905) all part of this exhibition. In 1871 the painter settled in Argenteuil and in 1879 he moved to Vétheuil with his wife Camille, and their two sons Jean and Michel who was still a baby. Here the painter experienced one of the hardest periods of his life: his beloved wife fell ill and died September 5, 1879, and the winter that followed was to be the coldest France had ever had. The artist’s sense of isolation is reflected in the pictures dating from that period: powerful paintings expressing Monet’s attempt to immortalise the terrible cold by means of rather unreal colours, so different from the realistic tones he had used for his views of Argenteuil. In paintings such as Snow Effect, Sunset (1875) and Vétheuil in the Fog (1879), we see how Monet gradually abandoned description and ventured into the realm of interpretation and simplification of the subject. Between 1880 and 1885 he regularly sojourned in Normandy where he grew up and had learned to paint en plein air with his first teacher Eugène Boudin. The sea, the beaches, the cliffs of Pourville, Étretat and Varengeville are subjects that meet his aesthetic endeavours. In paintings such as The Sailing Boat, Evening Effect or Cliffs and the Porte d'Amont, Morning Effect, both from 1885, landscape is no longer a mere representation of a static scene. The texture is thick, brushstrokes are long: “earth and sea are forces in action, captured at the height of their clash”. As Monet’s letters confirm, the play on light variations reflect the artist’s marked sensibility for natural elements which he tries to convey on the canvas. In The Beach at Pourville, Setting Sun (1882), the artist describes the landscape at dusk capturing the fleeting effects of light on the surface of the water. The artist returned to Normandy in 1917 the same year he painted Boats in the Port of Honfleur, the very last painting he completed away from Giverny. In late 1883 Monet and Renoir undertook the first of a long series of journeys. In January, the two artists travelled along the Mediterranean coasts following Cézanne’s footsteps and then Monet headed alone towards the Liguria Riviera. The painter was particularly taken by the region’s “shimmer”, “magic light”, and colours: “everything is so colourful and golden, it is marvellous and the countryside is everyday more beautiful, I am spellbound”. This sense of marvel translated into paintings with an unusual palette (The Castle of Dolceacqua, 1884). In a letter to Berthe Morisot Monet wrote he was “eager to visit Brittany”, which he did in the autumn of 1886 settling in Belle-Île. The first contact with the Atlantic Ocean deeply moved the painter who had grown up on the coasts of Normandy: “I find myself in a superb and savage region, with piles of terrible rocks and a sea of incredible colours”. The island’s wild nature inspired the artist to paint about forty works depicting the ceaseless battle between sea and water along the shores of this rugged coast. Human figures very rarely appear in Monet’s production and are mostly of secondary importance, and whenever a figure does happen to be the main focus of the picture, the individual is described with “the same rich and coarse texture the painter employs to represent nature”. On Belle-Île, Monet met critic Gustave Geffroy who would become the painter’s biographer and one of his most enthusiastic supporters. In 1889, Geffroy accompanied Monet to Creuse to pay a short visit to poet Maurice Rollinat. Monet was thrilled by the setting: “It’s splendid here, this incredibly wild region reminds me of Belle-Île”. The Bridge at Vervy is a composition skilfully built on the contrast between the whiteness of the facades and the rich vegetation described with a palette of blue and dark brown nuances. While the marines of Belle-Île represent a gradual and intuitive approach to the exploration of a subject through a series of paintings, the nine canvases painted in Fresselines, depicting the landscape around the confluence of two rivers, the Petite Creuse and the Grande Creuse, are a deliberate study around this concept (The Creuse Valley, Evening Effect, 1889). The series was for Monet a way of investigating different light conditions at different times of the day and representing the various levels of contrast that the same landscape could offer. Water Lilies “My garden is a slow labour of love, and I must say I am proud of it”. On November 19, 1890 Monet became the owner of a “house plastered in pink” in Giverny where he set up his first atelier and started to relandscape the garden as a tableau vivant, creating the setting that would become the much-loved subject he would paint until his death. The artist who was a keen gardener, transformed the area by planting fruit trees and wild flowers, such as nasturtiums, poppies, forget-me-nots, and other rarer flowers such as roses and Japanese cherry trees, agapantus, iris, many of which are well represented in this section. Plants become the subjects of his art: in 1893 Monet obtained the authorisation to dig a pond at the far end of his property where he could “grow the water plants” which he planned to depict in his paintings. This water garden, which Monet landscaped as a painting, represents the transposition of the way the artist dreamt of living. Between 1899 and 1902, Monet dedicated two series of paintings to his lily pond in which the backdrop is entirely invaded by a lush vegetation forming a screen offset by the coloured blotches of the water lilies. Monet’s new painting projects led in 1897 to the setting up of a second atelier, a colourful and flower scented realm, where in 1903 Monet started the water lily series. These flowers transformed into a real obsession for the painter becoming an independent subject. In 1902 Monet redesigned the lily pond turning it into his last and perhaps most accomplished creation. The pond, providing an endless source of inspiration originated the vast decorative cycle that was to be displayed at the Musée de l’Orangerie after the artist’s death. The paintings included in this exhibition can be considered as preparatory studies for the monumental panels, revealing a hidden side of Monet’s work leading to one of the painter’s most important works and providing important information on his panoramic compositions. The Japanese Bridges and Weeping Willows

The last two decades of Monet’s life and production are marked by a great expressive freedom and yet aggrieved by several losses. The artist witnessed the death of all those who had been at his side throughout his long life: in 1899 he lost his step-daughter Suzanne, in 1911 his “beloved companion” Alice Hoschedé. The death of the latter caused great pain to Monet who after this loss was incapable of painting for two whole years. His firstborn Jean died in 1914. The declaration of war and the diagnosis of a double cataract added to his sorrow. In the privacy of his garden, Monet produced a weeping willow series as a way of brooding over the anguish and the sadness that afflicted him. Monet felt a special bond with this particular tree: the artist had personally planted several exemplars of willows on the banks of his water garden and used to spend hours contemplating them. In the series painted between 1918 and 1922, the pond, the sky, the clouds and the flowers disappear and the focus of the composition is drawn to the solitary tree trunk and the undulated branches, with the surface of the canvas covered by a vertical pouring of colourful vibrations. With a marked modulation of light and shade, Monet accentuated the presence of the tree that occupied the entire surface of the small-size canvases that seem barely able to contain the plant’s vitality. The series of paintings dedicated to the Japanese footbridge and the path of rose trellises represent a surprising phase of the painter’s output. In these very personal pictures, the subject seems to disperse and what comes to the surface is the rhythm of the brushstrokes and the amplitude of the gesture, giving rise to an explosion of colours whose density and intensity make the actual image almost unreadable. The only distinctive element in the two series is the slender arch at the centre of the composition, covered in a lush vegetation that fills the space. What counts for Monet are light, air, and all that exists between the subject and his eye. The concept of painting not what the painter sees but rather vision itself opens art to modernity. The Monumental Panels In 1914, encouraged by his great friend and father of the nation Georges Clemenceau, and by Blanche, the stepdaughter who stayed by him during his last years, Monet undertook the monumental project of the Grand Decorations. To celebrate the end of World War I, the painter of Giverny offered the Nation a series of twenty panels on the theme of water landscapes, which were to be placed, according to the artist’s instructions, in two oval rooms inside the Musée de l'Orangerie in the Tuileries Garden. In 1915, Monet had built at the northeast end of his property a third twenty-three metres long atelier, that measured twelve metres wide and fifteen high. This space was designed especially for him to work on the Grand Decoration. Monet used to work simultaneously on various paintings, some of which he retouched after years, until his death, and therefore it is impossible to outline an exact chronology. Monet painted a considerable number of paintings for the Grand Decoration, but only a part of them was selected to be displayed at the Orangerie. Many paintings of the Musée Marmottan collections were to be part of that colossal project. The Wisteria paintings (1919-20) for instance, were part of the Grand Decoration but the artist decided not to include them in the series nor the several two by two panels that were supposed to link much larger canvases measuring between four and six metres long. The selection put together for this exhibition underlines the expressive eloquence of the last phase of Monet’s career and focuses on the oscillation between figuration and abstraction that could be rightfully defined as “non-figurative art”. Blue tones are predominant in these paintings, a circumstance that is believed to be related to the painter’s condition. Monet in fact confessed “I see everything blue, I no longer see red and yellow: that annoys me terribly because I know these colours exist. I know that on my palette there is red, yellow, a special green and a particular purple: I don’t see them as I used to, but I remember them well nonetheless”. The initiative is promoted by Generali Italia – sponsor of the exhibition – through the Valore Cultura programme, a project that sets out to attract families, youths, clients, and employees to the world of art by offering reduced tickets to exhibitions, theatre shows, events, and art and culture related activities. The exhibition also counts on special partner Ricola, technical sponsor Trenitalia, official colour Giotto, icon brand F.I.L.A. Fabbrica Italiana Lapis ed Affini, and media partner Radio Dimensione Suono. The event is recommended by Sky Arte HD. The catalogue is published by Arthemisia Books. Opening times Monday to Thursday 9.30 - 19.30

Tickets Full € 15,00 (audio guide included)

Information and group bookings Official hashtag | |

In the garden

In the gardenThe initiative, which is scheduled to run from June 26th to September 13th, 2020, is inaugurating a temporary space for art in Corso Matteotti 5, in Milan, in the very heart of the city.

Modigliani and the Montparnasse Adventure

Modigliani and the Montparnasse AdventureOn 22 January 1920 Amedeo Modigliani was taken, unconscious, to the Hôpital de la Charité in Paris and died there two days later at the age of only 36, struck down by the then incurable disease of tubercular meningitis that he had miraculously managed to survive twenty years earlier.

Madonna di Campiglio - Pinzolo - Val Rendena Travel Guide

Madonna di Campiglio - Pinzolo - Val Rendena Travel GuideThe Brenta Group of the Dolomites and the perennial glaciers distended on the granite peaks of the Adamello and Presanella encase the Rendena Valley, running up to the crowning charm of Madonna di Campiglio.